The human psychology in comprehending and adequately responding to disaster risk remains one of the toughest nuts to crack for the nation's weather and emergency management professionals. The National Hurricane Center forecasted a major landfalling hurricane somewhere along southwest Florida more than four days in advance; emergency management professionals and even Governor DeSantis implored more than 2.5 million residents to heed evacuation calls. (1)

And yet, the death toll stands at several dozen and continues to climb. (2) Beyond better predictions, the devastation in human lives and property damage wrought by Hurricane Ian in southwestern Florida will prove to be yet another unfortunate case study for social science communities to tackle, and they will likely focus on three major factors: COVID migrations, a false sense of risk, and shifting risk.

New to Florida: COVID drives population migration unfamiliar with hurricanes

COVID and the benefits of sunshine, low taxes, and remotely working in a tropical paradise like Florida have surged population across the state since 2020. COVID "migrants" from New York, New Jersey, California, and elsewhere have flocked to the state to the tune of 574,000 added in 2021, a 40% increase compared to even 2020, according to the Florida Department of Transportation. (3) Fort Myers, where Ian struck hardest, has seen its population surge more than the rest of the state, and it is part of an overall trend for the area the past 60 years. (4)

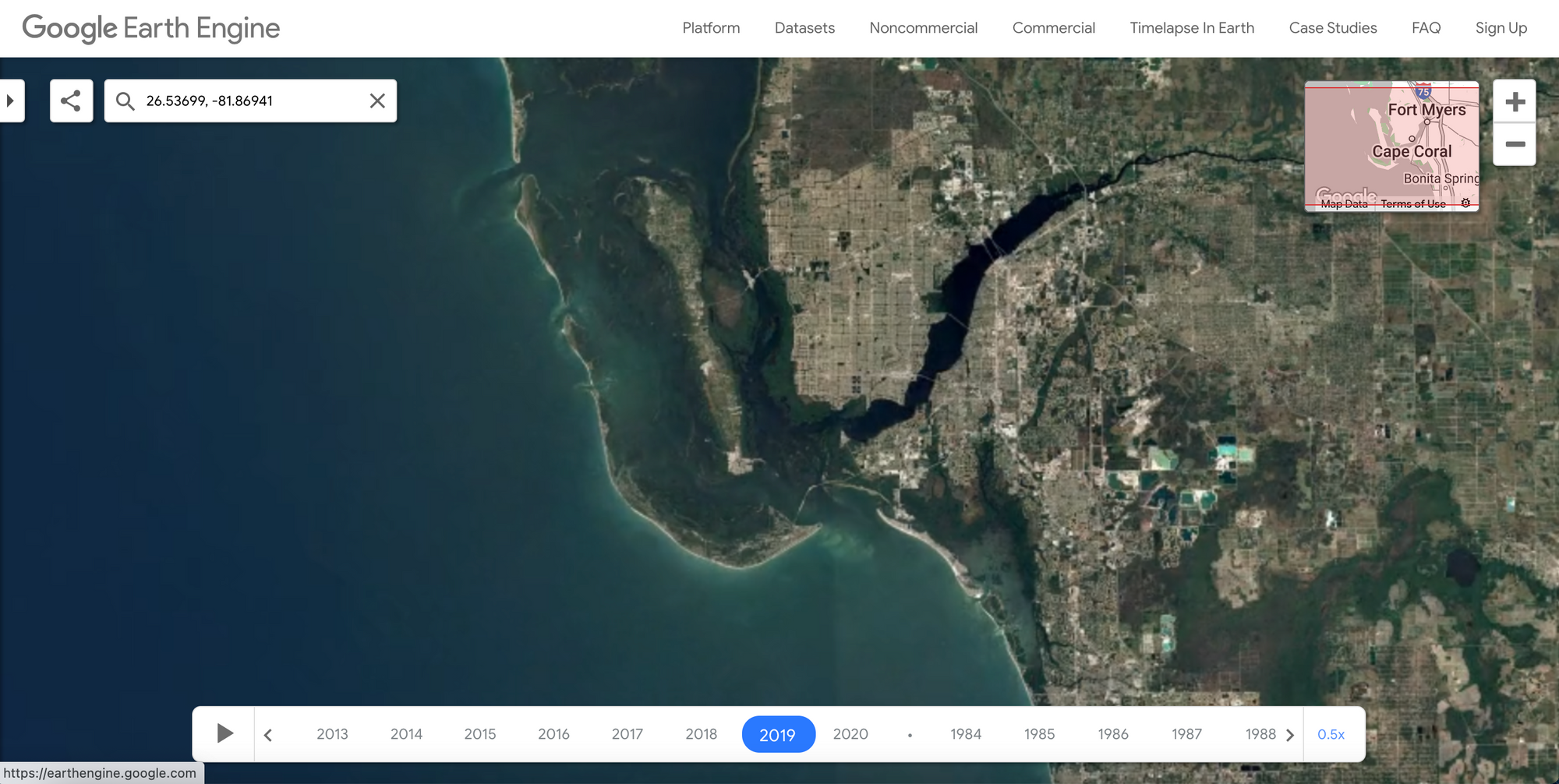

When Hurricane Donna struck the region in 1960, the Fort Myers metro area sat at 54,539 people. The population has nearly doubled every 20 years since, as seen in a Landsat timelapse of development, and as of the 2021 census now sits at nearly 790,000. (5) Even tiny Sanibel Island, which was shredded by Ian, has seen its own explosive growth going from just 100 people in 1960 to more than 6,300 today. (6) This new Florida population brings a surge in unfamiliarity with the risks and complex decisions like evacuation or preparation that hurricanes bring.

Once bitten, twice shy: past hurricane evacuation experience clouds judgment

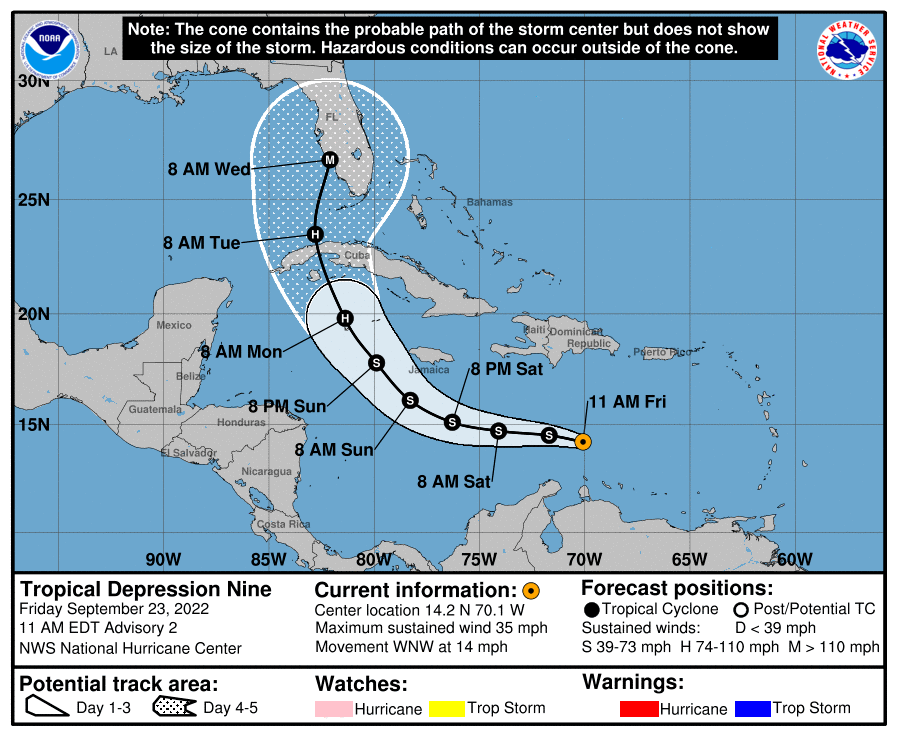

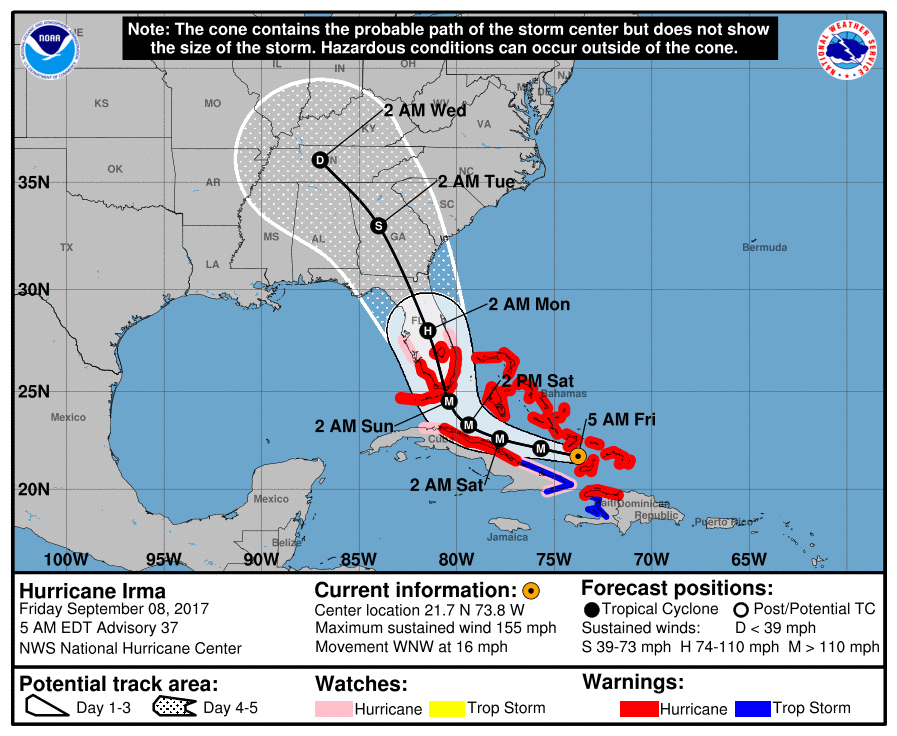

Longer-term Florida residents might be used to the threat of hurricanes, but that long-term memory can also sabotage normal risk processing. In 2017, massively intense Hurricane Irma formed well into the Atlantic and lashed Puerto Rico and other Caribbean locations before targeting the entire Florida peninsula. Dire emergency management messages like "Get out now" were heeded by nearly one-third of the state.

For one, it had been some time since Florida had been directly struck by a major hurricane, and viewers could see the massive scale of the storm and the destruction to Caribbean locations. The result was a run on water, gasoline, and other commodities, log-jammed highway systems, and long overnight commutes for millions of evacuees on both sides of the peninsula.

The cost for those who choose to evacuate is not trivial with some studies indicating households who have the means may spend upwards of $1,200 on transportation, lodging, food, and lost wages. (7) Some vulnerable populations simply do not have the means to evacuate. By the time Irma arrived in Florida, the punch it packed was a shadow of its former self and not nearly as intense as originally predicted. When a population experiences a deluge of crisis messaging that does not see or feel it at the "crisis" level communicated, it deludes one's sense of risk. As a result, the Irma experience for many created a presciently nightmarish psychological scenario where evacuee veterans swore to never evacuate again. (8)

Shifting Risk: improvements needed for hurricane impact prediction and communication

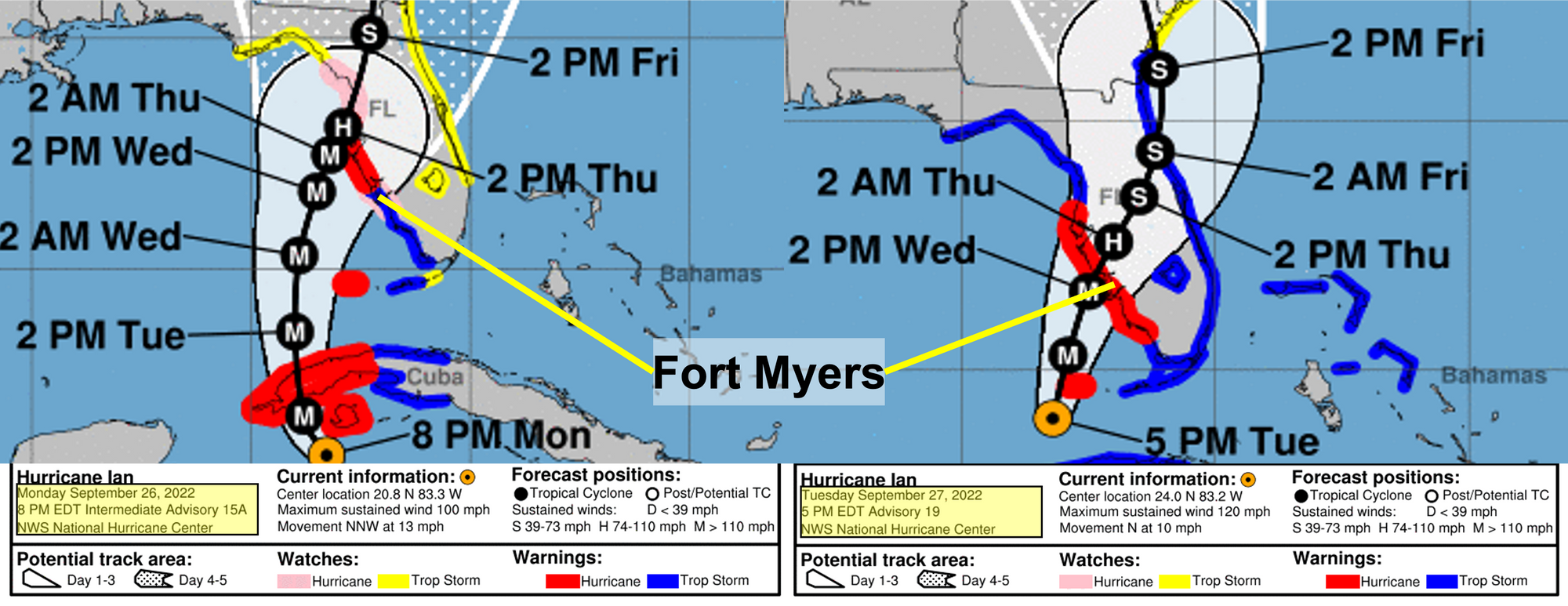

130 miles. That is approximately how far Hurricane Ian's predicted center track shifted in the final 30 hours before landfall. Despite messaging from the Hurricane Center to avoid fixating on the exact track, communities and people still base their evacuation decisions on the best track our nation's hurricane professionals provide. And despite Fort Myers sitting within the infamous "cone of uncertainty" (albeit at the very edge most of the time) the shift in impacts over those 130 miles is enormous. With a track nearly overhead around Clearwater on Monday, I evacuated my family. Ian obviously passed well to the south and other than a few branches down in the yard, an evacuee like me could psychologically conclude I do not need to evacuate in the future.

For the Fort Myers and Naples areas though, the track's 100+ mile shift southward in less than 36 hours afforded those communities little time to process preparedness and evacuation decisions as storm surge forecasts went from about 5 feet to over 15 feet overnight. A lot of scrutiny is being placed on Lee County's evacuation orders that were not mandated until 24 hours prior to storm arrival (of note: Lee County mandated evacuations at least 48 hours prior to Hurricane Irma's landfall in 2017). (9) A 2015 report from The Conversation chronicles the "Should I stay or should I go?" conundrum, saying "the limits of our [storm surge] forecasting technology fit with the limits of human preparation." (10) In other words, the final storm surge preparation for Fort Myers and Naples with tripled storm surge potential did not come into full focus for residents until it was too late, especially after overnight hours are subtracted out (afterall, people still need to sleep).

A perfect storm

The result was a perfect psychological storm: a surge in population unfamiliar with hurricane preparedness, a resident population skeptical on the benefits of evacuating yet again, and a shift in risk that left many with inadequate time to evacuate even if they had the means. It remains to be seen just how many left, but future studies are likely to show that fewer evacuated for Hurricane Ian than the 2.5 million urged by emergency officials. On Sanibel Island alone, where a historic 12- to 15-foot storm surge engulfed the island which is now cut off from the mainland, at least 200 households refused to evacuate.

In addition to calls for improving scientific hurricane predictions like these, NOAA, the emergency management community, and academia must continue to prioritize the psychology of risk communications in warning populations. (11) Sites like the Florida Disaster portal are good, but official prediction information and community messaging still remains siloed and often difficult for residents to find and navigate the flood of information. (12) A lot will be learned from Hurricane Ian. We must be better at understanding the psychology of risk so we can communicate it better and save lives in the future.

References:

- 1. https://www.wctv.tv/2022/09/27/more-evacuations-ordered-hurricane-ian-churns-toward-floridas-gulf-coast/

- 2. https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2022/09/30/hurricane-ian-live-updates-death-toll-damage-path-forecast/8133688001/

- 3. https://www.palmbeachpost.com/story/news/2022/02/08/covid-pandemic-brings-people-new-york-and-new-jersey-florida/9203825002/

- 4. https://fortmyers.floridaweekly.com/articles/viral-migration/

- 5. https://earthengine.google.com/timelapse#v=26.53699,-81.86941,10.354,latLng&t=3.6&ps=50&bt=19840101&et=20201231&startDwell=0&endDwell=0

- 6. https://sanibelmuseum.org/cover-page/brief-history-and-timeline-of-sanibel-and-southwest-florida/

- 7. https://abcnews.go.com/Business/people-evacuating-hurricane-ian-face-dire-financial-choices/story?id=90630756

- 8. https://www.jacksonville.com/story/news/2017/09/18/irma-evacuation-nightmare-next-time-some-may-not-leave/15773471007/

- 9. https://www.leegov.com/irma/documents

- 10. https://theconversation.com/should-i-stay-or-should-i-go-timing-affects-hurricane-evacuation-decisions-40141

- 11. https://thehill.com/opinion/national-security/3667162-hurricanes-like-ian-are-a-growing-national-security-threat-we-need-better-prediction/

- 12. https://www.floridadisaster.org/

Member discussion: